What is Genre?

Pauline J. Grabia participates in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program, and earns from qualifying purchases from links in this post.

Please subscribe to my email newsletter for updates on my website and blog, and exclusive access to exclusive material in the Subscriber Content page of this website (see menu bar above). New content will be added regularly. You can sign up in the form found in the footer of this page. Thank you!

My Illumination

Yesterday, I realized what genre is and why it’s important to understand genre as a writer. Well, perhaps not quite, but close. It wasn’t until recently that I investigated the meaning of the word genre and its significance, and it has radically changed the way I approach literature both as a writer and a reader. I lacked a true understanding of what genre is. Thanks to reading The Story Grid: What Good Editors Know by Shawn Coyne, “Understanding Genre: How to Write Better Stories” by Savannah Gilbo, as well as numerous other articles and blogs on the internet, I learned that genre was more than just a category that a type of book fell into, or the sign in a bookstore that designated where various styles of books could be found. For example, the Science fiction/Fantasy or Romance sections of the library or bookstore. If this is your understanding of what genre is, allow me to illuminate you. This blog post will not be an exhaustive review of genre. Rather, it will attempt to define it and show examples.

What is Genre, anyway?

I learned primarily from Storygrid.com that genre, simply put, is about value. It’s what the protagonist of a story wants and needs and how the story unfolds to describe the protagonist’s journey to obtain those wants and needs. All human beings have felt wants and needs that we consciously or unconsciously pursue. These can be understood by looking at a concept called Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. It’s an idea in psychology presented by Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” that explains people’s motivations or drives based on meeting their needs, listed in a hierarchical order from the most basic or primal of needs to the most advanced best represented by a pyramidal structure with Physiological needs (food, water, shelter, warmth, rest) at the base and self-actualization needs at the top (fulfillment, one’s own potential). In fiction, as in life, the characters have needs and desires that fit within this framework, and they pursue those wants and needs in various ways, which makes up the story's plot.

Confused yet?

Put more simply, genre is the value at stake as the protagonist (and other characters) pursue their felt wants and needs based on Maslow’s Hierarchy.

As you can see, genre is more complicated than simply sorting and classifying stories based on the elements and scenes they share. Genre communicates to the reader what to expect and feel when they read the story (or watch the TV show or movie).

I’m about to present a genre courtesy of Savannah Gilbo in her above-mentioned article on Savannahgilbo.com. I highly recommend her blog to anyone who is a student of writing.

Genre can be broken into two basic types: Consumer-facing and Content.

Consumer-Facing Genres: These are sales categories. These dictate where a book will be found when sold online or in a brick-and-mortar. There are many categories, but a few examples include science fiction, fantasy, young adult, and women’s fiction. They give us an idea of certain elements that make up the books that fall under these categories. Still, these tell us nothing specifically about the genre of a story, understanding that genre is about a value, a method of communicating feelings and expectations to the reader.

Content Genres: These involve the types of content in a story, with corresponding obligatory scenes and conventions (elements) that work together to produce an emotional/psychological experience in readers.

Obligatory scenes are scenes that the reader consciously or unconsciously expects in a story to ‘work’ or make sense. These are genre-specific and, as the name indicates, obligatory. They must be in a story for it to be in that specific genre and for the story to feel complete. For example, an obligatory scene of a story in the horror genre is the Hero at the Mercy of the Villain/Monster scene. Readers will be put off if this scene is missing from a horror story. They’ll put the book down in dissatisfaction.

Conventions are elements that must exist in a story to be considered part of a certain genre—things the reader expects to find in that story. A convention of a thriller story is that there must be a MacGuffin—the Villain’s goal or object of desire, why they do the evil things they do. The villain’s motivation is essential to understand. Without this convention in place, the story doesn’t make sense.

Content Genre can be further broken down into external content (value) genre and internal content (value) genre.

External Content Genre vs. Internal Content Genre

The following examples are from the book The Story Grid: What Good Editors Know by Shawn Coyne.

The External Content Genres: These are made up of plot-driven stories that are mostly driven by interpersonal or internal conflict.

· Action (Star Wars, Jaws, Jurassic Park)

· Horror (IT, The Shining, The Omen, Alien)

· Crime (Murder on the Orient Express, The Godfather, Double Indemnity)

· Western/Eastern (Lonesome Dove, Unforgiven, Tombstone)

· War (Searching for Private Ryan, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket)

· Thriller (The Silence of the Lambs, The Fugitive, Gone Girl)

· Society (Animal Farm, 1984, Thelma and Louise)

· Love (Pride and Prejudice, The Notebook, Bridget Jones Diary)

· Performance (Rocky, Chariots of Fire, The Karate Kid)

The Internal Content Genres: These are character-driven stories where the drive comes from inner conflict within the protagonist and other characters.

· Worldview (Juno, The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Oedipus Rex)

· Status (Oliver Twist, Milk, Gladiator)

· Morality (Wallstreet, Drugstore Cowboy, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest)

It should be noted that a story can have both an external and internal content genre. However, the author must choose which of these will be the primary genre and which will be the secondary genre. Otherwise, the author will lose focus when writing, and the story will meander hopelessly.

Shawn Coyne presents the idea of the Five-Leaf Clover of Genre to understand the clear categories of genre that “identify, meet, and innovate story requirements.” (Story Grid.com) The five leaves include:

· Content (see the section above that describes External and Internal Content Genres)

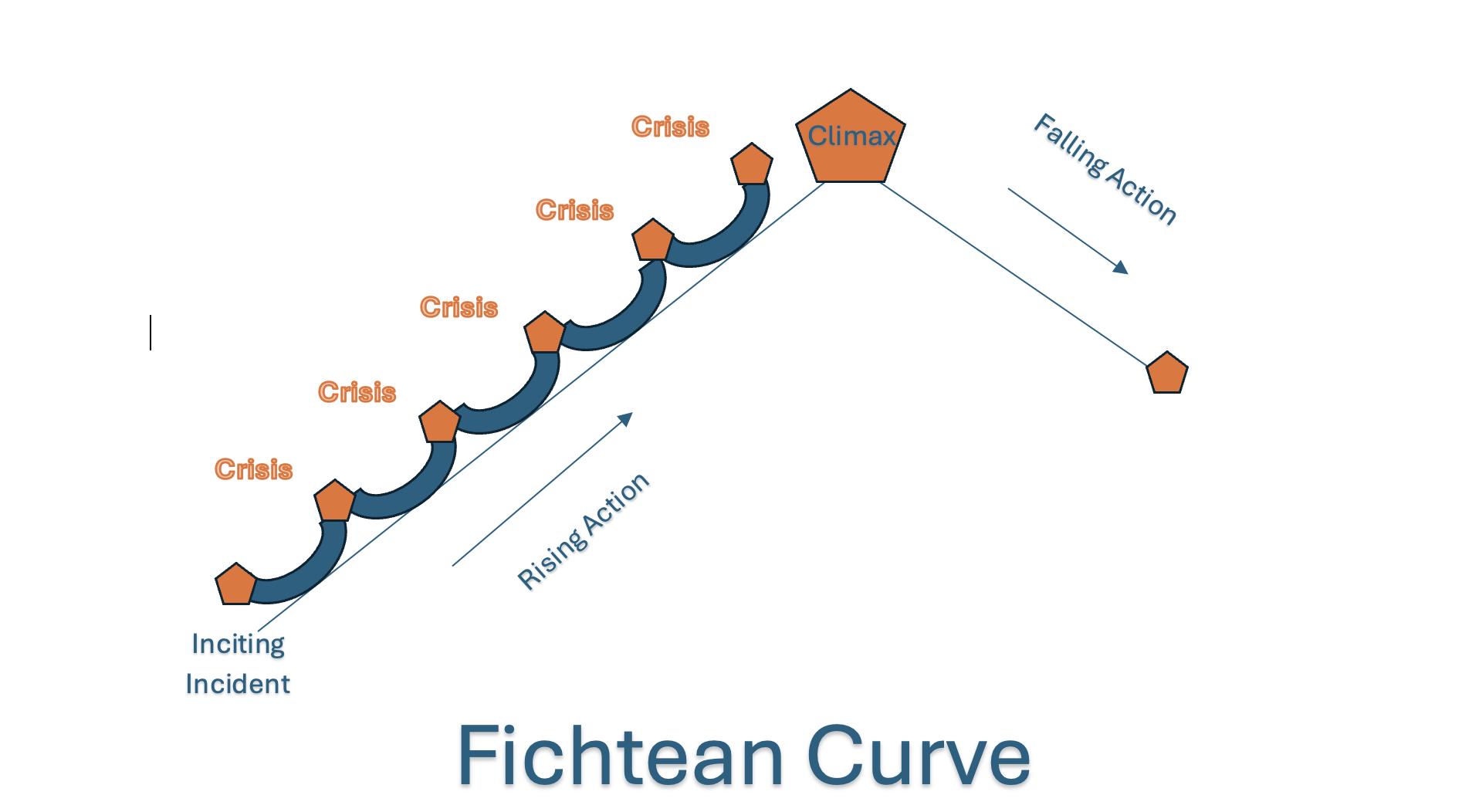

· Structure (Archplot, Miniplot, Antiplot)

· Style (e.g., Comedy, Drama, Musical)

· Reality (Fantasy, Realism, Factualism, Absurdism)

· Time (Short-form, Medium-form, Long-form)

For more information on these five categories, I suggest you read the book Story Grid: What Good Editors Know by Shawn Coyne. There is too much information to cover in this post.

Why Should Writers Care about Genre?

Without an idea of their story’s genre, a writer loses sight of the overall shape and form of what they’re writing. From the introduction to the conclusion, there will be no clear definition of the change that must take place for the protagonist (and other characters). Genre helps define the objects of desire for the protagonist and the antagonist. Without understanding these, the reader can’t figure out what the story is about. Why are the characters doing what they’re doing? What’s the motivation? Reading a story without a clear genre is like watching a cat chasing its own tail. It might initially amuse the reader, but after a short time, the reader wonders, “What’s the point?” They won’t know what to expect from the story or what feelings they are supposed to experience. Frustrated, they’ll put the book down and move on to something else.

If you want to write a story that makes sense, feels complete, and is a page-turner that the reader can’t put down, you must have chosen a clear genre and understand that genre thoroughly.

Are you writing a story and aren’t clear on the genre? Have you read a book where the genre wasn’t clear, and it frustrated you? What books with clear and well-developed genres have you read? I’d like to hear about it in the comments section.

Please subscribe to my email newsletter. By subscribing, you will receive advance notice of upcoming blog posts, news updates about my website and publishing journey, and exclusive content available only to subscribers on my Subscriber Content page. This content currently includes the Prologue and Chapters Eleven through Twenty-Five of my novel Filling the Cracks, the first ten chapters available to the public on my blog. If you want to read the novel's conclusion, subscribe! If you haven’t read Filling the Cracks, you can begin with Chapter One here.

Thanks again for reading! Check out my social media accounts and return for another informative post next week. God bless you richly!

Pauline J. Grabia

Consequence is a word with weight.

Often, we think of consequence only as punishment or fallout, something negative that follows a poor choice. But when I write Stories of Consequence, I’m drawing on another meaning entirely. Here, consequence means significance. Weight. Importance. I write stories that matter because they grapple honestly with darkness while still testifying to the reality of light made possible through God’s grace.